By Kiara Doyal, The Seattle Medium

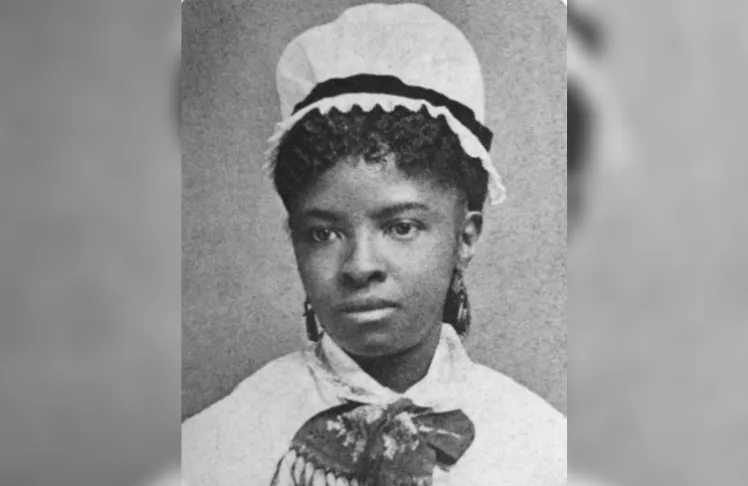

Mary Eliza Mahoney, born in 1845, was a pioneering African American nurse and one of the first African American women to earn a professional nursing degree. Driven by a passion for promoting equality for both African Americans and women, Mahoney dedicated her career to encouraging greater equality for African Americans and women.

Throughout her life, Mahoney faced many racial and gender barriers, yet she still became one of the most prominent African American figures in the medical field. In the nineteenth century, Black women faced systemic barriers to formal training and career opportunities as licensed nurses, but Mahoney knew from a young age that she wanted to be a nurse.

During this era, nursing schools in the South rejected applications from African American women. However, there was a greater chance of acceptance in the Northern parts of the country, so Mahoney set her sights on the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

At the time, domestic service was typically the only job opportunity for a Black woman, and initially, the New England Hospital hired Mahoney as a maid. However, after spending 16 hours a day, seven days a week ironing, scrubbing floors, and cleaning, Mahoney worked her way into the nursing program.

In 1878, at age 33, Mahoney was admitted to a 16-month nursing program alongside 39 other students. Of the 40 enrolled, only she and two white women successfully completed the program and earned their degrees. Graduating in 1879, Mahoney became one of the first Black women in the United States to receive formal nursing training.

After earning her diploma, Mahoney built a distinguished career as a private nurse, primarily caring for wealthy white families. Despite the deep-seated racial biases of the time, Mahoney was highly respected for her professionalism and dedication. In an era when African American nurses were often treated as household servants, she set clear boundaries to reinforce her professional role, including eating separately from household staff—an act of self-respect in the face of persistent racism.

One former patient expressed deep admiration for Mahoney in the American Journal of Nursing, stating, “I owe my life to that dear soul.” Her dedication to her craft elevated the status of nursing as a whole and helped shift perceptions of African American women in the medical field.

But Mahoney’s legacy goes far beyond her nursing excellence. She was a lifelong advocate for racial equity in healthcare. In the early 20th century, the American Nurses Association (ANA) barred Black nurses from membership. In response, Mahoney co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) in 1908, an inclusive organization committed to fighting racial discrimination and promoting the professional development of nurses of color.

Her success opened doors for future generations of Black women in nursing, and she would devote the rest of her career to making the profession more accessible, particularly through her role at the NACGN.

Mahoney finished her career serving as director of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum for Black children in Weeksville, Brooklyn, where she served freed Black children and the elderly using the knowledge she gained over the years.

During her retirement, Mahoney was still active with women’s equality and a supporter of women’s suffrage. In 1920, after women’s suffrage was achieved in the U.S., Mahoney was among the first women in Boston to register to vote at the age of 76.

In 1923, Mahoney was diagnosed with breast cancer and battled the illness for 3 years until she died on January 4, 1926, at the age of 80 at the New England Hospital for Women and Children—the same hospital where she started her nursing career. Mahoney never married and did not have any children, as she chose to dedicate her life to nursing and activism.

Mahoney’s contributions were formally recognized in 1936 when the NACGN established the Mary Mahoney Award, which continued after the NACGN merged with the ANA in 1951. The award remains one of the ANA’s highest honors, given to individuals who make significant strides toward improving opportunities in nursing for minority groups.

In 1976, Mahoney was inducted into the American Nurses Association Hall of Fame, and in 1993, she was welcomed into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

Mahoney’s commitment to improvement, personal growth, and constantly pushing herself to achieve is reflected in her lifelong guiding motto, which was, “Work more and better the coming year than the previous year.”