By Sofia Schwarzwalder, The Seattle Medium

Diana Quintero-Perez was 10 years old the first time she walked into the free homework help program at the Lake City branch of the Seattle Public Library.

Some 14 years later, Quintero-Perez can still be found at homework help each Thursday. She’s a tutor now, and a first-generation college graduate who obtained her bachelor’s degree in 2023 in education, communities and organizations, a major in the University of Washington’s education department.

Her first higher education hurdle came while Quintero-Perez was still in high school: navigating the college-admissions process. Families with the financial means often hire private college counselors. But a 2024 pricing survey conducted by CollegePlannerPro found the average hourly rate was $224 nationally and $226 on the West Coast.

That isn’t a realistic option for many first-generation or low-income students who often lack other kinds of help through the college-application process. As a result, they rely on the few free college readiness resources and organizations on school campuses and off.

Quintero-Perez, 24, grew up in a Spanish speaking household. Her mother and father, who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico, did not receive education beyond middle and elementary school, respectively. When Quintero-Perez was in elementary school, her parents weren’t able to help explain homework assignments.

One afternoon during the 2011-2012 school year when Quintero-Perez was a fifth grader at John Stanford International School, her parents took her to Homework Help at the Lake City library branch.

The program supported Quintero-Perez through her next seven years of school, during which she attended Eckstein Middle School, Jane Addams Middle School and Nathan Hale High School.

When the time came to apply for college, Quintero-Perez said tutors she saw everyday at Homework Help served as her main resource. The volunteers helped her study for the ACT, reviewed drafts of her personal statement and read over scholarship applications.

“It’s a very lonely time when you start applying to these universities, scholarships and applying to FAFSA,” Quintero-Perez said. “My parents didn’t understand whatsoever what was going on. My friends didn’t understand either.”

The Seattle Public Library (SPL) offers free homework help and tutoring at nine locations across the city at the Broadview, Columbia, Douglass-Truth, High Point, Lake City, New Holly, Northgate, Rainier Beach and South Park library branches.

Volunteer tutors are available to students on a drop-in basis to help with any school-related work they have, ranging from first-grade math to college-application essays. Last year 650 tutoring sessions served 6,146 students across the nine branches, according to data provided by Elisa Murray, a communications strategist for SPL.

“We try to attract volunteers who are from the neighborhoods that are going to be served by homework help,” said Murray, who noted that 80% of students who participated in end of year surveys reported speaking a language other than English at home. “Because it’s really helpful for students to be with people from their own communities.”

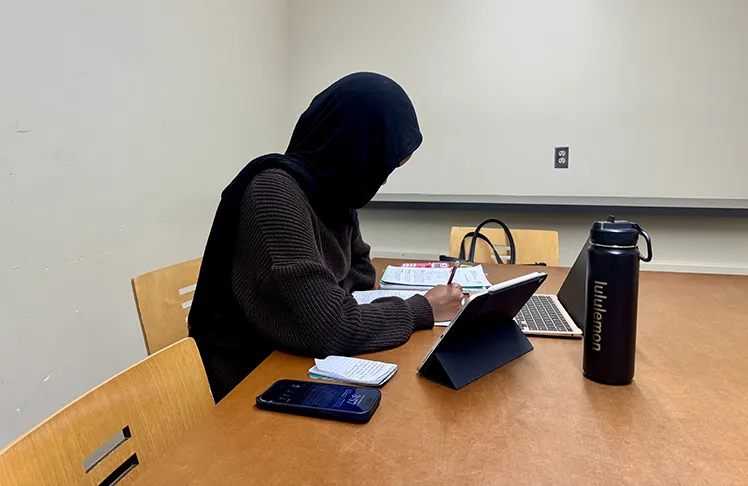

And sometimes former students return to give back. Quintero-Perez is now a research interviewer at Fred Hutch Cancer Center where she interviews participants in both English and Spanish. But every Thursday night from 6 to 7:30 p.m. she can be found tutoring students at the Lake City branch.

“What I receive, I want to give it back twofold,” she said. “One of those things is giving back by supporting other students with their homework because I know how important this is.”

At Seattle Public Schools, counselors serve as the main point of contact for students through the college process. At Garfield High School, the student body of more than 1,600 students come from a wide variety of economic backgrounds.

“We have some students that are working with private college counselors that do not need much extra support,” said Daniel Lee, a counselor in his 13th year at Garfield. “We also have about a 40% free and reduced meal population.”

Those students and their families don’t have the privilege of affording private college counselors, Lee explained. As a result, they often rely most heavily on the resources and programming offered for free at the school.

Lee and the team of counselors at Garfield visit 11th and 12th grade classes to discuss graduation requirements, hold open hours to help students with questions on college, scholarship or financial-aid questions and organize visits with representatives from different universities. They are also responsible for other student body wide counseling duties that are not related to college.

“We do need more resources in terms of filling gaps for students that don’t have the advantage and privilege of having a private college consultant,” Lee said.

On Garfield’s campus two community based organizations – College Possible and Upward Bound – provide college readiness support to cohorts of students. College Possible provides free mentoring and coaching to low-income students to help them get into college, and Upward Bound supports students who are both low-income and first-generation. Students can be accepted into the Upward Bound program as early as the summer before ninth grade or as late as their senior year.

Upward Bound is one of eight TRIO programs that provide federal support and services for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. A report from the 2024 fiscal year showed 1,026 unique Upward Bound projects across the country, like the one at Garfield, received funding. But more than 120 Upward Bound programs have since shut down after their funding was cut under the Trump Administration.

Roberto Lopez is in his 11th year as the TRiO Upward Bound counselor at Garfield. He’s spent the last 25 years of his career working with first-generation students.

Lopez himself was a first-generation college student from a low income family. He studied and eventually went into accounting but felt something was missing from his career. He found a sense of belonging volunteering with students and decided to make a career shift.

At Garfield, he can serve 53 students at a time. Students apply into the program and are accepted as space becomes available.

He explained that each student has different goals – some want to go to top schools, and they have: last year two students went to Princeton and Brown. Others want to stay in state.

Upward Bound helps to fill the gap for students who can’t hire a private consultant. They help students identify what they want, what is realistic and the road map to get there. “You don’t know what you don’t know,” Lopez said repeatedly, explaining why hard working students don’t always see success.

Lopez said counselors at Garfield have caseloads ranging from 350-400 students. It’s no fault of the counselors, Lopez said, but kids do slip through the cracks.

“The system is designed for maximum efficiency, so counselors don’t always have the time,” Lopez said. “If you’re a student who is first gen and aspiring to go to college and you don’t have anybody in the building to say ‘Hey, are you trying to go to college,’ it can be daunting.”

Lopez and Lee agree more resources are needed to support all students through the process.

“There are so many barriers,” Lopez said. “It’s genuinely stacked against the student who may truly be doing everything they can. But sometimes it’s just dumb luck that they find out about programs.”