By K. Barrett Bilali

Urban News Service

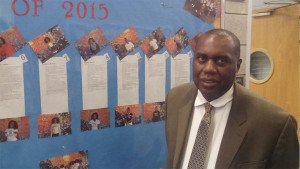

As a first-time principal, Dr. Michael Wiltshire was assigned in 2001 to one of America’s worst government-run schools. At Brooklyn’s Medgar Evers High, only 60 percent of students graduated, and 24 percent of all pupils reached college. The school’s enrollment was low, at just 600 students, of whom 99 percent were black. Yet with dogged determination and stringent reforms, Wiltshire did what few thought possible: He turned the school into an institution of academic excellence.

Wiltshire previously chaired the math and science department at Long Island’s Islip High School. Its students were 99 percent white, and 100 percent of them advanced to college.

Wiltshire was hired to lift Islip’s math scores, which had slid to a 77 percent passing rate. In fact, Islip’s superintendent reminded Wiltshire that “the real estate in our community depends on our schools” — the higher the test scores, the higher the home prices.

At Medgar Evers, however, Wiltshire found no urgency to boost its statistics. The school was mediocre, and that seemed OK.

“No ethnic group has a monopoly on intelligence,” said Wiltshire. “That is what made me go to work. I went to work to change the trajectory of this school.”

Wiltshire lengthened Medgar Evers’ school day from 7:10 a.m. to 3:15 p.m. and arranged after-school educational programs. He established a Saturday academy and mandatory summer school. It became a year-round center of learning.

“The first thing we had to do was change the culture,” said Wiltshire. “The school had a narrow curriculum with students just getting by on the basics.”

He set new graduation requirements with more rigorous course study: Four credits of science, four more of math and at least one Advanced Placement class. The school emphasizes math, science and technology, yet students now enjoy athletics and performing arts classes. Students must maintain an 80+ GPA.

Wiltshire phased out the ninth-through-12th grade high school model. He added sixth through eighth grades as an early high school. These students followed the high school curriculum and even took New York State’s demanding Regents exams. Ninth and 10th grades were considered high school. And “early college” began in 11th grade.

The school even got a new name: Medgar Evers College Preparatory School.

The difference was “night and day,” said assistant principal for science Delroy Burnett, who preceded Wiltshire at Evers. “Yes, some teachers resisted,” said Burnett. “But they left the school. They were not ready for a more rigorous curriculum.”

With the community and parents seeing positive results, enrollment expanded from 600 to 1,261 students. Good education has a price tag, said Burnett. With more students, the district provided more money.

Wiltshire recalled a parent who came in to consult him privately. She wanted no obstacles to hinder her ninth-grader. “The family was living in a shelter,” said Wiltshire. “Four years later, the boy was salutatorian of his class. Now he’s in a doctorate program in pharmacy.”

That story echoed Wiltshire’s education. His mother was a visionary, Wiltshire said. She wanted to become a teacher herself, but her dreams did not outpace their abject poverty in Jamaica. “I learned from my mom that an education is the greatest gift you can give a child,” said Wiltshire.

“Medgar Evers College Preparatory School is a shining example of how prepared students, given access to challenging courses and supported by their teachers, school administrators and families, can achieve at the highest academic levels,” says Trevor Packer, senior vice president of the College Board’s Advanced Placement instruction.

This now-90-percent black school today has a 96-percent graduation rate, and 79 percent of graduates enter college. It now offers 20 Advanced Placement courses. Its math and reading scores exceed the citywide average, according to Insideschools.org.

“We have just had six students accepted into Cornell, one into Harvard and four into NYU,” said Wiltshire.

Recognizing his results at Medgar Evers, school officials recently tapped Wiltshire to save another failing Brooklyn campus. Boys and Girls High School, which graduated singer and actress Lena Horne, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm and jazz pianist Randy Weston, is now among the worst spots in America’s largest school district. It’s now known mainly for dropouts and plunging test scores.

Wiltshire now shuttles between these two places. He is acting principal of Boys and Girls High and maintains his office and title at Medgar Evers.

But Wiltshire faces yet another major challenge: He has until no later than 2018 to repair Boys and Girls High School or New York State will padlock this historic institution.